Astronomers have confirmed that Albert Einstein was right about black holes. They found a region around black holes, called the “plunging region,” where matter falls in as Einstein predicted.

Using powerful telescopes that can detect X-rays, a team of researchers observed this plunging region for the first time in a black hole located about 10,000 light-years away from Earth. Andrew Mummery, the lead author of the study published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, explained that this area was previously overlooked due to lack of data.

This isn’t the first time black holes have supported Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The first-ever photo of a black hole captured in 2019 also confirmed Einstein’s idea that gravity bends space and time.

Over the years, many of Einstein’s predictions, like gravitational waves and the speed limit of the universe, have been proven correct. Mummery, a researcher at the University of Oxford, emphasized that Einstein’s track record makes him hard to doubt.

The team specifically searched for this plunging region, despite doubts from others in the scientific community. Confirming its existence is a significant achievement and adds to the growing body of evidence supporting Einstein’s theories.

In an artist’s drawing, a black hole pulls material from a nearby star, creating a spinning disk that encircles the black hole before it gets sucked in.

“Just Like a Waterfall’s Edge”

The black hole we observed is part of a system called MAXI J1820 + 070. This system includes a star smaller than the sun and the black hole itself, which is estimated to be 7 to 8 times the mass of our sun. Astronomers used NASA’s space telescopes, NuSTAR and NICER, to gather information about how hot gas, called plasma, from the star is drawn into the black hole.

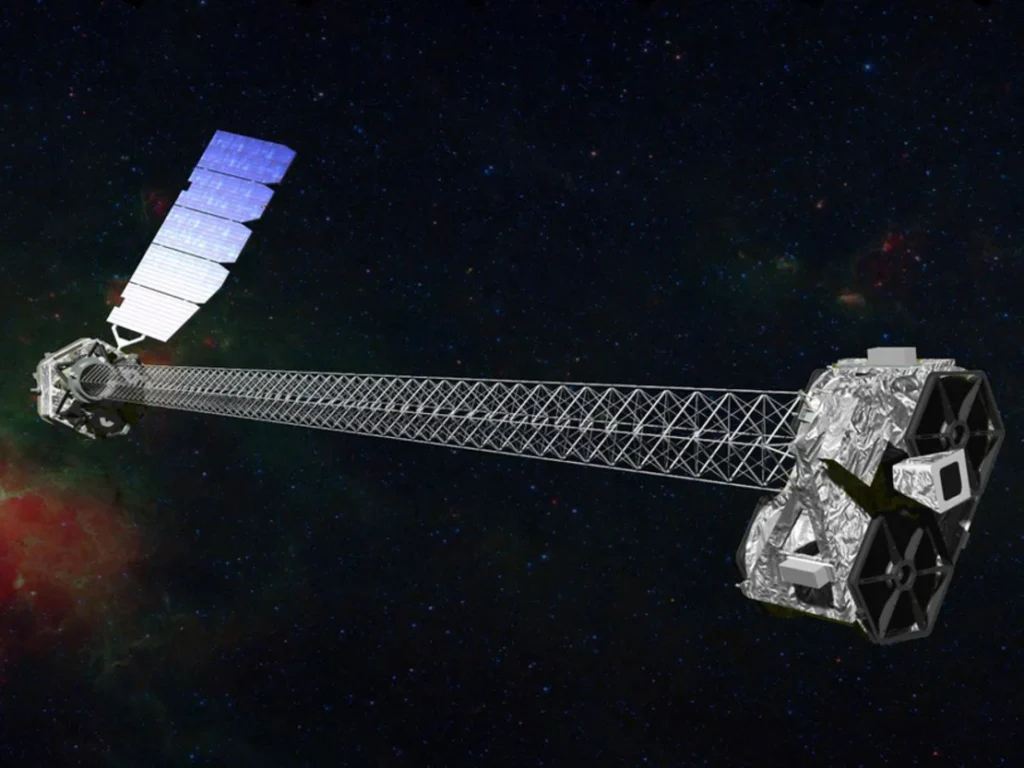

NuSTAR, short for the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, orbits around Earth. NICER, also known as the Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer, is located on the International Space Station.

NASA’s NuSTAR telescope, shown in this artist’s illustration, was used for the first time to find the “plunging region” near a black hole.

Mummery compared the area around black holes to a river. Most of the material from nearby stars forms stable discs that flow smoothly, like the river. However, there’s a small region at the edge, called the “plunging region,” which is like the edge of a waterfall. Here, the support disappears, and everything crashes headfirst into the black hole. While astronomers have seen the “river” before, this is the first evidence of the “waterfall.”

Unlike the event horizon, which is closer to the center of the black hole and traps everything, including light and radiation, in the plunging region, light can still escape. However, matter is inevitably drawn in by the strong gravitational pull.

Understanding this region could help astronomers learn more about how black holes form and change over time. “Studying this region gives us valuable information because it’s right at the edge,” Mummery explained.

Mummery compared the space near black holes to a river, where most of the material from nearby stars flows smoothly in stable discs, like water in a river. However, there’s a small area called the “plunging region” at the edge, similar to the edge of a waterfall. Here, everything crashes headfirst into the black hole because the support disappears. This discovery of the “waterfall” is new, even though astronomers have known about the “river” for a while.

Unlike the event horizon, which is closer to the center of the black hole and traps everything, including light and radiation, in the plunging region, light can still escape. However, matter is pulled in by the strong gravitational force.

Understanding this region better could help astronomers learn more about how black holes form and change over time. Mummery explained that studying this area is crucial because it’s right at the edge.

A Connection to the Past

According to Christopher Reynolds, a professor of astronomy at the University of Maryland, finding proof of the “plunging region” is a big step forward. It will help scientists improve their understanding of how matter behaves around a black hole. Reynolds, who wasn’t part of the study, says it could even help measure the rotation speed of the black hole.

Dan Wilkins, a research scientist at Stanford University in California, finds this discovery exciting. He notes that in 2018, one of the black holes in our galaxy emitted an extremely bright burst of light, along with an excess of high-energy X-rays.

Wilkins mentioned, “Back then, we thought the extra X-rays came from the hot material in the ‘plunging region,’ but we didn’t know exactly how it would look.” He wasn’t part of the new study either.

This new study actually calculates that, he explained. It uses Einstein’s gravity theory to predict how the X-rays from the material in the “plunging region” would appear around a black hole. Then, it compares these predictions with the data from the bright burst in 2018.

Wilkins believes this area of study will be very important in the next ten years. He said, “As we wait for the next generation of X-ray telescopes, we’ll learn a lot more about the innermost areas just outside black holes’ event horizons.”